In 1993, when HarperCollins released an omnibus edition of Charles Wright’s slim, hallucinatory novels of the 1960s and ’70s, the author hadn’t published any new fiction in two decades. His three books—The Messenger (1963), The Wig (1966), and Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About (1973)—had been successes by any reasonable measure: published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux; reviewed in the New York Times; and praised by James Baldwin, whose enthusiasm was quoted at length on the back cover of the new volume. “Charles Wright is a terrific writer,” Baldwin wrote, having already listed The Messenger among Dostoyevsky, Henry James, and Richard Wright in a 1964 list of formative reading experiences. “I hope he goes the distance and lives to be 110.”

Wright had been a columnist for the Village Voice, where much of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About was originally published as nonfiction, but now he seemed to be a casualty of New York’s grimmest modern era. The short bio on the HarperCollins collection promised that he was working on a follow-up, which never materialized. When he died in 2008, his obituary revealed that Wright had been living in a spare room of his editor’s apartment since 1976.

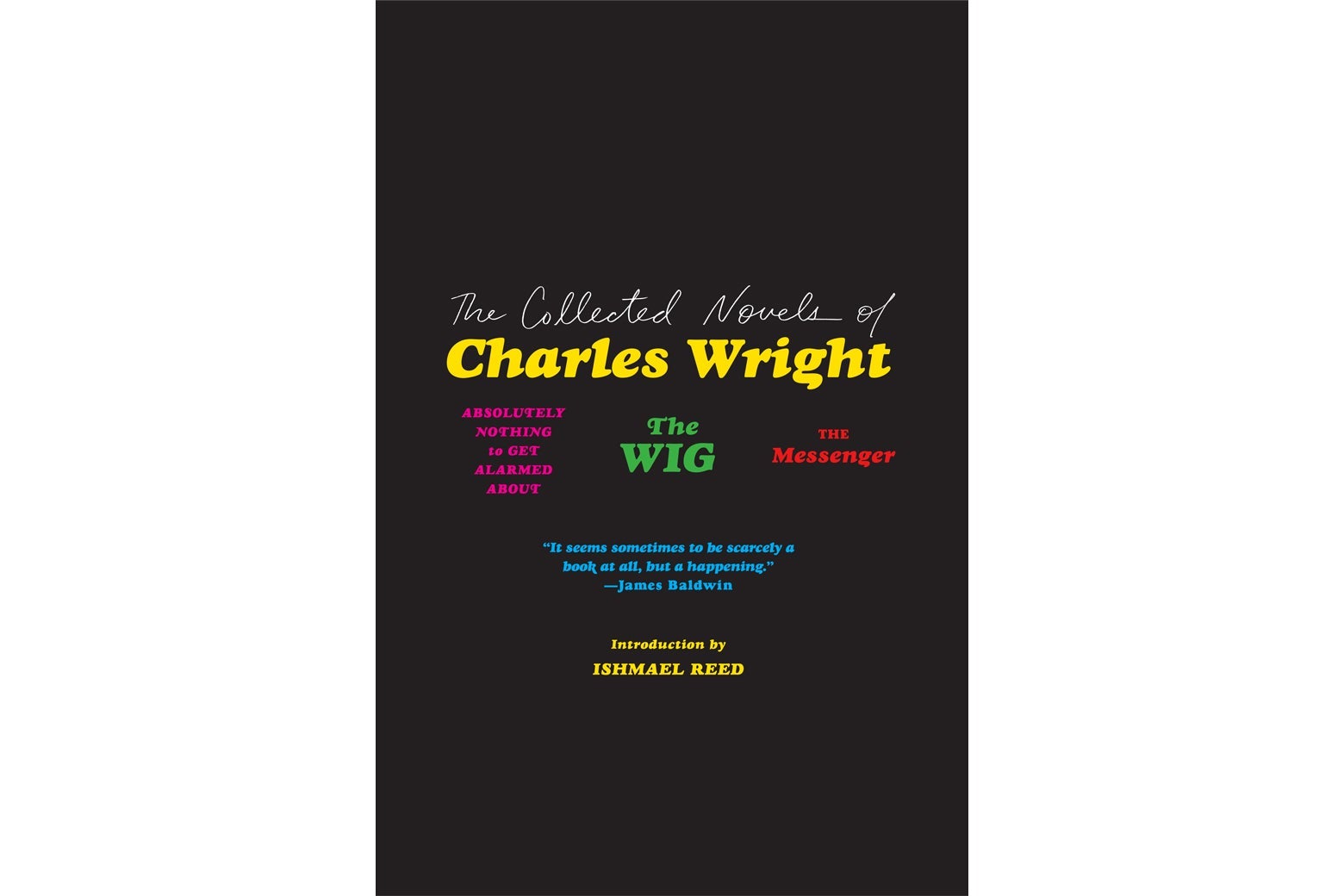

This month, The Collected Novels of Charles Wright is back in print again, bearing an introduction by Ishmael Reed, whose own early work was so influenced by these madcap, angry farces that he has called himself Wright’s “younger brother.” It joins James McPherson’s Hue and Cry (1968) and George Cain’s Blueschild Baby (1970), both reissued this summer by Ecco after their own long out-of-print exiles. Even after the past few years’ and months’ plenitude of tributes to Baldwin and Toni Morrison, these books show that we still have more to learn about the emotional and stylistic breadth of black writing from this era. Wright’s, McPherson’s, and Cain’s books show just how multifaceted and varied black writing was at the era’s height. But their spotty publication history reminds us that the fate even of black genius is never secure. We can never take for granted that black artists will be consistently supported, even when they succeed.

The ’60s were so replete with breakthroughs in black self-expression that the decade was effectively defined by them. 1960 began with student-led sit-ins in Greensboro and Nashville, and the ensuing growth of the civil rights cause occurred simultaneously with a pop-chart takeover by Motown and Stax. The establishment of Harlem’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre in 1965 inaugurated the Black Arts Movement just as Black Power took hold in the public consciousness. Inevitably, our collective memory of this cacophonous decade is dominated by the groups and organizations that rose to prominence, from those famed record labels to Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Nation of Islam. But works of art aren’t made by movements, fiction least of all. These books are records of highly individual experience. They fight against any notion of group belonging.

Charles Wright was born in rural Missouri in 1932, 11 years before James McPherson and George Cain were born in Savannah, Georgia, and Manhattan, respectively. Their early lives were even more varied than the geographic differences might imply. The teenage Wright was a prolific hitchhiker who thumbed his way through the Southwest to California before serving in Korea and moving to New York. McPherson was a studious son of working-class parents who ascended to Harvard Law School. And Cain was a quintessential rose grown from concrete: A gifted basketball player, he attended private high school and received a college scholarship that appeared to be his ticket out of the urban underclass.

Heroin undid him, and Blueschild Baby is the record of that undoing. Over the course of a few days, his narrator, also named George Cain, muddles through the familiar paces of addiction literature: desperate attempts to score, harrowing attempts to quit, and a series of degrading violent episodes including an attempt to rape his daughter’s babysitter. In his foreword to this edition, critic Gerald Early positions Blueschild Baby among the era’s many black classics of self-education including Manchild in the Promised Land, Soul on Ice, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X; Cain’s dedication even includes an Arabic phrase, “Al-hamdu-li-la” (“All thanks to Allah”), that implies his life has changed. But there is no conversion narrative here, and no attempt to draw grand conclusions about society from this one character’s physical and existential torment. This is a novel about waste and abuse, the ways in which self-hatred radiates through a person and poisons his ability to honestly connect with others.

The book is plainly autobiographical, down to narrator George’s memories of basketball greatness and youthful promise. But its true power is linguistic: Cain’s prose moves according to its own logic, drawing readers into the memories and feelings of a person who has lived among squalor and suffering so long that he can’t differentiate the present from the past. The book I was reminded of, more than those youthful chronicles Early references, was Hubert Selby Jr.’s 1964 Last Exit to Brooklyn, which depicted drug- and abuse-filled neighborhoods in biblical, rolling sentences. Cain writes like he can’t pause to catch his breath:

Swilled hardily and the liquor settled a hot ball in the stomach, warming me all over. Watched dirty river, oil slicks colored rainbow, old rubbers, dead rats, floating upside down, wood, dead fish with white bellies. Use to swim here, me, Smitty, Tommy. Tommy drowned out here, head caught in a floating milk can. They dredged him up days later fish eaten and water blown.

The language of Blueschild Baby is disorienting, but the basic patterns of the “addiction novel” are still familiar. Charles Wright’s books function in the opposite way. The writing is conversational and often funny, but the narratives are impossible to predict, the tone impossible to pin down. All three novels are picaresques narrated by black men who traverse low-life New York in quick, two- to four-page vignettes. The episodic structure—the structure of the newspaper column—allows Wright to invent extravagant set pieces, like a rat-catching sequence in The Wig and an anything-goes bisexual orgy in The Messenger. He creates a city’s worth of junkies, hustlers, prostitutes, black Muslims, and strivers. It’s the world of Blueschild Baby, viewed aslant. Here, the world of scheming heroin addicts is but one aspect of a carnivalesque, semisurreal Manhattan, and Wright’s narrators never pause long enough to become fully ensnared by that lifestyle. He bounces between trysts with men and women, friendships and business deals with black and white, male and female. He is angry, but not on anyone else’s behalf.

Not even an artist as distinctive and occasionally inscrutable as Toni Morrison could avoid our compulsion to deify certain writers as “prophets” and sages on social issues, race especially. But Wright was truly no one’s spokesman. There are no potential bumper stickers here, no inspiring calls to action—not even a discernible philosophy, beyond ornery independence. He came by this attitude honestly: His Times obituary is a picaresque with odd heights—wartime service, raw journalistic talent—and long, sad gaps. He effectively dropped out of society, but lived for decades as a “second father” to his editor’s children.

By every measure, James Alan McPherson lived a more stable, comfortable, and remunerative life than Cain or Wright, from his nuclear family to his long-running professorship at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. But despite winning the Pulitzer Prize for fiction—the first ever awarded to a black author—for his second book, Elbow Room, McPherson was never a household name or a bestseller. His style is spare and subtle, and his characters’ inner worlds are so intimately depicted that grand social statements aren’t necessary. McPherson wrote the stories of Hue and Cry in his early to mid-20s, and they share a youthful sense of possibility—romances change, innocence is challenged, loyalties are tested. But there are no clichés anywhere near this book. McPherson’s stories are like slow-burn ballads.

The book ends with the title novella, a long-simmering tragedy of thwarted interracial love. The white protagonist, Eric Carney, is “a Quaker, and had been taught all his life to look for causes.” His sense of do-gooderism is inherited from his pacifist parents, and Eric interprets this as a mere calling to be a bland, “nice” person. But “then the Southern marches began,” and he leaves college as thousands of white liberal students did at the time, a journey that McPherson describes only through Eric’s scared, overwhelmed eyes:

It was a very small, very backward, very grievously sick Mississippi backwater town, and Eric walked in the dangerous parts of it for a semester and a summer, becoming very busy and very purposeful. Even after going into that town became a badge for people from other schools, much like himself, and even after he sensed the dissatisfaction of the local blacks with the many people of his maudlin sensitivity and perpetually understanding nature, he had tried to keep up his voter registration, community organization, and other works.

Eric falls in love with a black woman, Margot Payne, which challenges the limits of his family’s social progressivism. But the nature of their conflict is more elemental: Margot cannot trust that Eric’s devotion to her is separate from his “maudlin … perpetually understanding” commitment to black justice. How can two people share a trusting love when their worldview is so defined by the inequities between them? The personal and political stakes of 1960s racial attitudes are completely intertwined in these stories. The reader feels them equally.

There is no anger in Hue and Cry, and no easy sadness. McPherson’s characters—including a number of Pullman train porters, a cherished middle-class career track for urban black men in the late years of the Great Migration—struggle with commitments and communities of all kinds: family, jobs, mentors, co-workers, religious faiths. They are not heroic iconoclasts, just people acting by their wits and best intentions. Their glory comes from the care and thought of McPherson’s descriptions, and the easy music of his dialogue.

The Collected Novels of Charles Wright: The Messenger, The Wig, and Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About

By Charles Wright. Harper Perennial.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Charles Wright and George Cain lived for decades having never published anything after Watergate. James Alan McPherson, while hardly a wasted talent, published only nonfiction after Elbow Room. And beyond them: No new books have come from David Bradley since The Chaneysville Incident won the PEN/Faulkner Award in 1982, and Kathleen Collins’ short fiction and screenplays are only now being collected decades after her death. I was struck, too, by the name of the writer of the introduction to this edition of Hue and Cry, Edward P. Jones. The stillness in McPherson’s stories reminded me of Jones’ tales of black life in D.C. Jones is slightly younger than McPherson but was his student, mentee, and eventually fellow Pulitzer winner for The Known World. About 15 years ago, Jones was as well-known and revered as an unapologetically literary author can be in the United States. He continues to teach, but as far as I can tell, this very brief, largely personal introduction is his first published writing in more than a decade.

There is a tradition of sorts under which black artists are anointed as geniuses and then, afterward, too rarely heard from. It’s hardly restricted to literature, as the careers of Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, D’Angelo, and Lauryn Hill attest. There are various explanations for the fallow periods in these artists’ résumés and the longtime challenges to funding and distributing their work. But the trend itself attests that American cultural gatekeepers simply don’t value black art enough to nurture its makers. These newly reissued books offer a different view of The Sixties than we usually get; they force us to see individuals where our collective memory seeks out superheroes and crowds. Our challenge is to support the artists who are doing the same for us now—to keep them from needing future rescuing.